How well the mobile networks would handle the extreme amount of data traffic during the Justin Bieber concert has been an interesting question. So far, the answer is: really awfully.

22,000 Beliebers who contiguously shared pictures and videos are a gigantic challenge for the mobile networks. The operators have well in advance been aware that the data traffic capacities would be tight during the concert days, and people should better not rely on mobile phones to make appointments. At the same time, the operators did their best to provide the users the best-possible service. Additional base stations, upgraded transmission capacity and Norway’s fastest WLAN have been installed with large publicity. Probably, the mobile traffic capacity in and around the Telenor Arena represents the state of the art in April 2013.

Therefore, it is interesting to see what happened to the utilisation of the mobile networks during yesterday’s concert. Simula has two NorNet Edge measurement nodes (the picture below shows such a node) inside the Telenor Arena during the concerts. They are small computers that are connected to all the mobile network operators and measure the quality of the «mobile broadband» (we measure only data traffic, no voice or SMS). We performed two types of measurements and the results show that all operators had difficulties in providing a usable service.

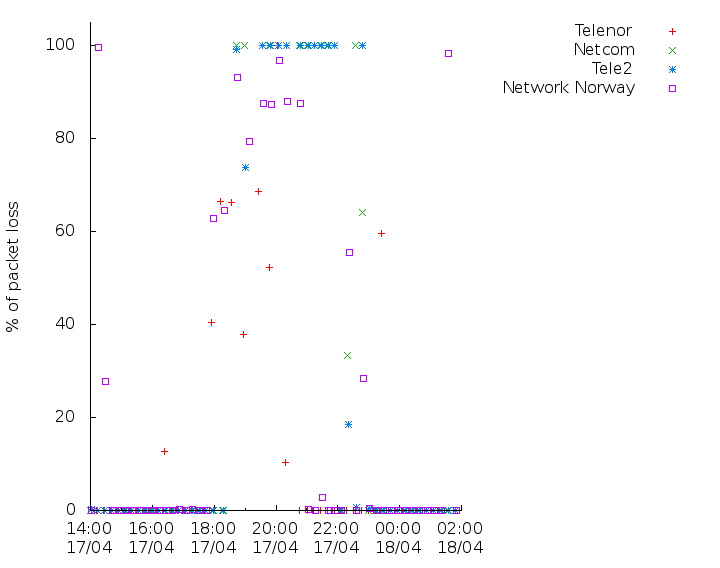

In the first of our measurements, we have tried to receive a data flow of 1 Mbit/s. We measured the packet loss, i.e. how many data packets that had been send from the server but have been lost on their way to the measurement node. The figure below shows that it is in the usual case not a problem for the mobile networks to handle such a flow. As soon as the doors to the concert arena had been opened, we see that the packet loss rises from 0% to 20-100%, and remains there until the end of the concert. The worst results are for NetCom (and Tele2 who have used their network during the whole concert). During large parts of the concert, no traffic arrived at our measurement node. This means that we were either unable to create a data session or (almost) no data packets came through the network. For Telenor (and Network Norway who used their network) was the situation partly somewhat better, but a packet loss over 20% made it difficult to use the network for something useful. The usual transport protocol in the Internet, i.e. TCP, reduces its bandwidth under such conditions to a bandwidth of nearly 0 bit/s. We have measured traffic on the path to the node (downlink), while there are many services that also require to send data as well. The capacity in this direction is even lower, and for that reason it can be assumed that the performance was even worse than we see in our figure. Telenor returned to almost normal operation about two hours before NetCom, which means that their network is better dimensioned for handling the load.

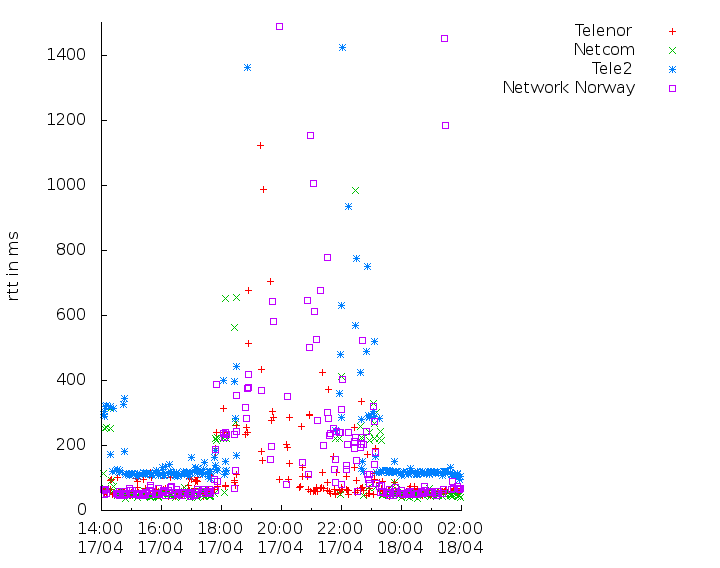

Another important parameter for the experienced quality in data networks is delay, i.e. how much time it takes before receiving a response from the peer. In our measurements see we a stable round-trip time (RTT) of under 100 ms before the concert. Such a delay is in most cases acceptable, and it will have low impact to the user experience of applications like e.g. Facebook or Instagram. During the concert, the delay exploded to multiple seconds at all operators. We have cutted the y-axis in the figure below at 1,400 ms, but there perceived delays were often more than 10 seconds. A consequence of such values are that most applications give up to wait for a response and report a failure. It is strange that the network operators configure their networks in a way that leads to such a delays. Data packets with these extreme delays should better be dropped instead.

For questions and further information, contact Amund Kvalbein <amundk@simula.no> or Kristian R. Evensen <kristrev@simula.no>.